Reading time: 11 minutes

Science fiction is one of the most flexible and diverse genres in fiction, and that’s why I love it. From post-apocalyptic dystopias to sentient trees with fish inside them, science fiction gives writers and readers the ability to set their own rules for the universe. It allows science fiction authors to explore big questions.

When you’re not hindered by slower-than-light space travel, you can explore new worlds. That means you can play with societies, physics and ethics that just don’t work here on Earth, or are perhaps too complex and sensitive to risk portraying in the context of reality. Readers are more willing to suspend disbelief to focus on the questions that you’re exploring when you are able to define the limits of the thought experiment.

Science fiction does not have to be lofty and profound to have an impact. Some of the greatest science fiction ever written has a sense of humor. Just look at Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. But even that rollicking adventure of flowerpots and paradox engines explores big questions. Adams subverts the genre by asking and then mocking the biggest question of all: what is the meaning of life?

As I build my science fiction editing empire, I’ve been on a quest to determine what makes good science fiction tick. I could begin all the way back in ancient mythology. Just try and tell me that a story about parallel worlds full of superheroes who determine the destinies of piddly little humans isn’t science fiction! But this is a blog post and not a book. Instead, I’ll just focus on a few key authors from the 20th century.

Big question: What if x and y were y and x instead?

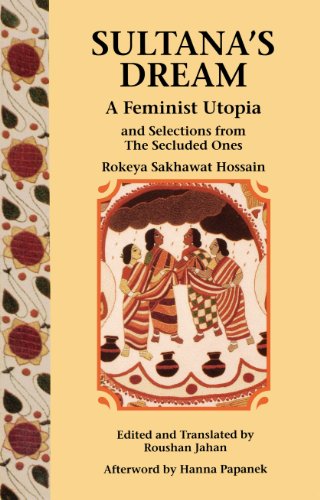

Case study: “Sultana’s Dream” by Rokheya Shekhawat Hossain (1905)

In her speculative story about a feminist utopia, Hossain explores the question of what it would be like to live in a society where the gender roles were reversed, and women held all the power. She takes that question and runs with it. In doing so, she creates a world that plays with the rules she knows as a woman living in Bangladesh, and flips them. Another author who did this well was Malorie Blackman, who flips the Black and White power structure of apartheid in Noughts and Crosses. You can also see it in Ursula K Le Guin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, which explores a society without the restrictions of fixed assigned genders.

Try it: Think of a binary relationship that we take for granted in our society, and then flip it.

Big Question: In the face of danger, can a society overcome its flaws?

Case study: “The Comet” by W. E. B. Du Bois (1920)

Du Bois helped to found the NAACP, and it should come as no surprise that his science fiction deals with themes of racism. In “The Comet”, the Black protagonist finds himself traveling through New York City with a White woman, the two of them the sole survivors of a catastrophic event. While they grapple with the paradigm shift of conflicting societal taboos and their need for human connection, Du Bois examines whether a society that is racist can overcome its prejudices in order to survive.

This is one of the key themes in many apocalyptic stories, and can be seen in Avatar, as well as in the trope of the Monstrous Other (where maybe humans were the real monsters all along).

Try it: Consider using your story to address a great wrong that you see in society.

Big question: What is the nature of reality?

Case Study: “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” by Jorge Luis Borges (1940)

Science fiction can bend minds as well as reality, and Borges is famous for his mind-melting use of nonfiction elements to build believable, academic labyrinths of possibility. It’s hard to even call “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius” a story when it takes the form of interconnected encyclopedia entries and academic correspondence. Through it, Borges creates “evidence” of a unique and contradictory world. When it was published, it became even more believable as Borges’ contemporaries played along, writing about the places he had invented as if they were real.

Similarly, by applying Nozick’s Experience Machine to a modern context, The Matrix explores the nature of reality and perception. And let’s not forget the classic blunder of the radio play of War of the Worlds. It was so realistic that it convinced an entire country that an alien invasion was underway. Here in Ecuador, the local adaptation led to riots. If your story can convince readers of a different way of perceiving reality, then you have made an impact. You will be remembered.

Other authors who have been influenced by Borges are Philip K. Dick and Thomas Pynchon.

Try it: Forget everything you know about reality, and create it anew, subverting all the rules and expectations. Can you create a coherent, convincing world with its own rules?

Big question: How can this situation be shown from a perspective that is different from the “default”?

Case Study: “The Liberation of Earth” by William Tenn (1953)

Some of the best science fiction stories are allegories, or commentaries on current events. We’ll probably see a surge in pandemic stories within the next five years, as well as “trapped in a room” stories, as the collective consciousness processes the Covid-19 pandemic.

In this case, Tenn tried to represent the effect of the Cold War on the inhabitants of the places where the war was physically fought. He used his depiction of the destructive liberation (and “re-liberations”) of Earth as two alien superpowers battle each other. He specifically wanted to “point out what a really awful thing it was to be a Korean (and later a Vietnamese) in such a situation.” Science fiction gives writers and readers the opportunity to inhabit perspectives that differ from their own, and this can have real power.

This is even better when the perspectives are own voices authors.

Try it: Take a situation from the news, history or your own experience. Try portraying it from the other side. Put it on a different world, or flip the rules.

Big question: What if we change one variable?

Case Study: “Surface Tension” by James Blish (1952)

Blish uses pantropy (the concept of human genetic modification for purpose of survival on other planets) to explore how societies evolve. “Surface Tension” covers multiple generations of a new, tiny human society, formed from microscopic cellular organisms underwater. Many people think that the “science” in science fiction refers only to the technology or machines that we use, but other disciplines can be a rich source of inspiration.

Our world is full of weird and unexplained things (fungus that turns ants into zombies, perhaps? Chemical secretions floating in the clouds above Venus?), and changing one variable in the great experiment of life can fuel a whole creative universe. Keeping abreast of current scientific discoveries helps science fiction authors to stay relevant.

Try it: Dive down the rabbit hole of Wikipedia and scientific journals. Find something new and interesting. Take that key element and apply that variable to your universe.

Big Question: Which driving motivational force is stronger, x or y?

Case Study: “The Longest Season in the Garden of the Tea Fish” by Jo Miles (2020)

Jo Miles’s story about sentient trees that live through a symbiotic relationship with tea fish that inhabit their cores is magical and strikingly original. However, just being unique isn’t enough to carry a story; what really gives this story impact is the tug between love and duty.

Finding strong motivational forces that are at the core relatable to any reader means that you can connect with your reader on a deeper level. Then you can build a story around the conflict of satisfying those themes, which pull against each other. The most common dichotomy in science fiction is the struggle between good and evil. Good science fiction authors know that it’s not the only option.

Try it: Place two important themes in opposition in your world. Explore how your characters shift the balance of them.

Big question: How far can this go?

Case Study: “Prott” by Margaret St Clair (1953)

St Clair is dazzlingly original and as early as 1950 she was pushing back against the trope of humans saving the universe through clever problem-solving that was prevalent in pulp science fiction. Her flair for the absurd and her unashamed authenticity give her stories the weird flavor that can be found in Douglas Adams’, Neil Gaiman’s and Iain M Banks’ writing. She created her own twisted logic and then pushed it to its limits, as in “Prott”, where a scientist becomes mentally unhinged through the act of observing alien life forms.

Try it: Throw caution to the wind! Make your own damn rules, then see how far they can go while keeping the universe and story coherent. It’s fine to break the rules of reality. You just need to make sure your logic, however bizarre, is consistently applied to your world.

Does science fiction have to address the big questions?

No. It’s perfectly fine to write a gripping good-vs-evil adventure through time and space. Readers enjoy stories about heroes using their wits and shiny gadgets to overcome the forces of evil. Science fiction is a broad genre, and anything is possible. However, asking big questions in your story can add depth and originality. Big themes resonate with readers. Using them helps your book to stand out from the crowd of similar heroes’ journeys, post-apocalyptic dystopias, and battle-royale caste systems.

With the exception of “The Longest Season in the Garden of the Tea Fish,” all the stories I have mentioned in this post are included in The Big Book of Science Fiction, edited by Ann and Jeff Vandermeer. It is a wonderful collection of stories by some of the greatest minds in science fiction through history.

If you’d like help digging deeper into your story, request a developmental edit or manuscript critique.

Links to books in this post are Amazon affiliate links.

One Response